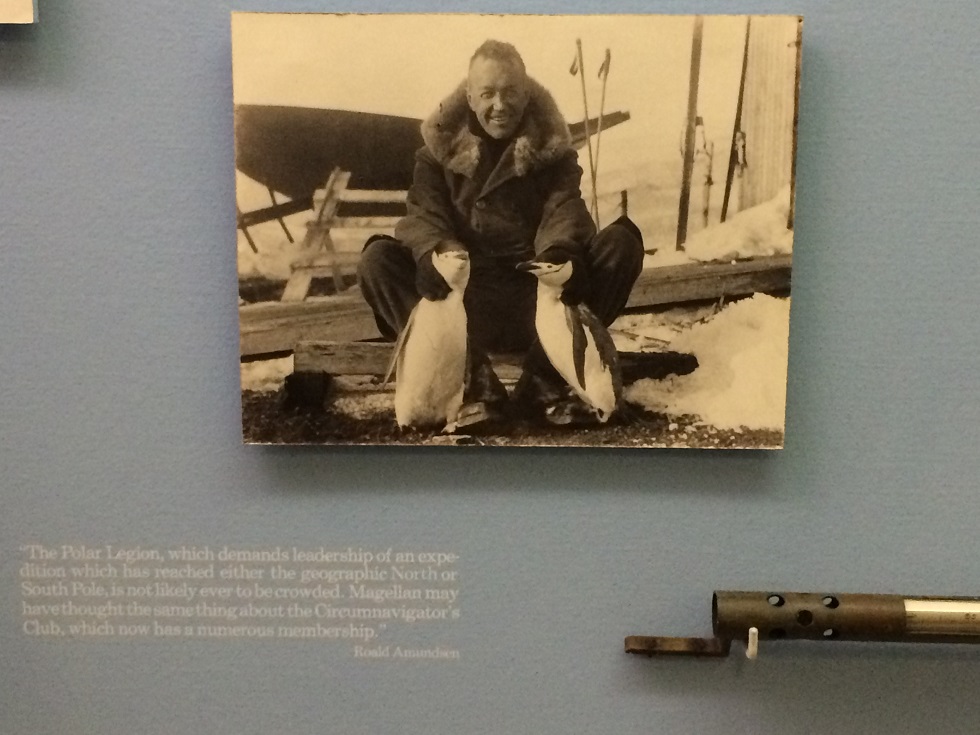

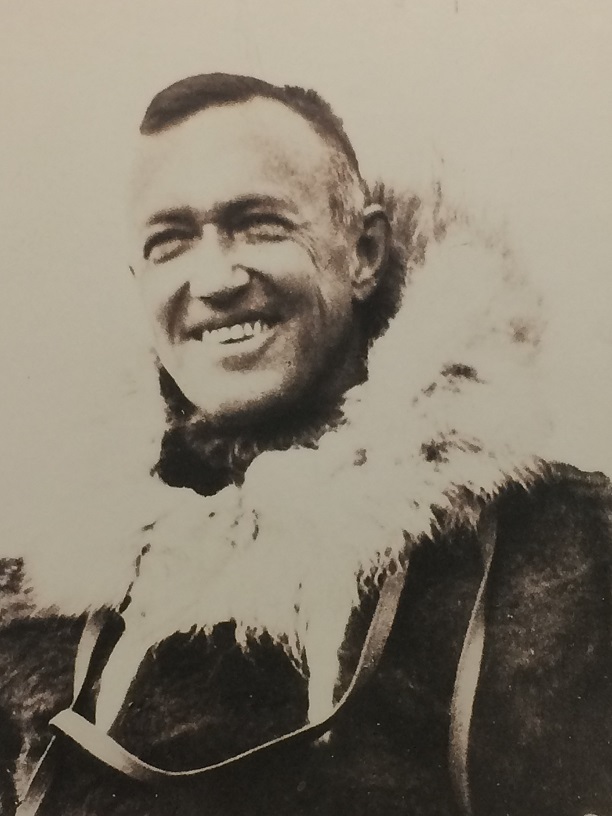

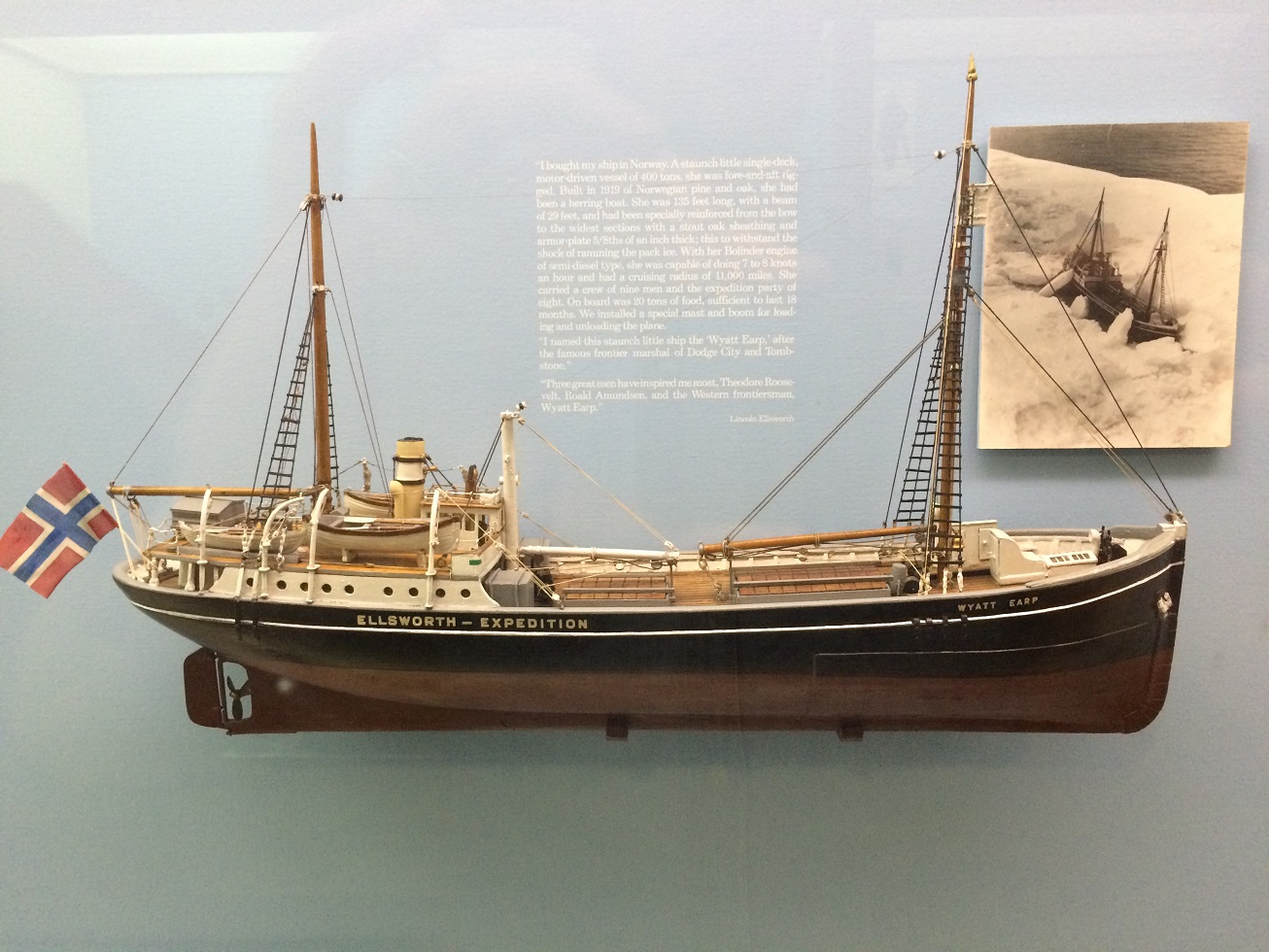

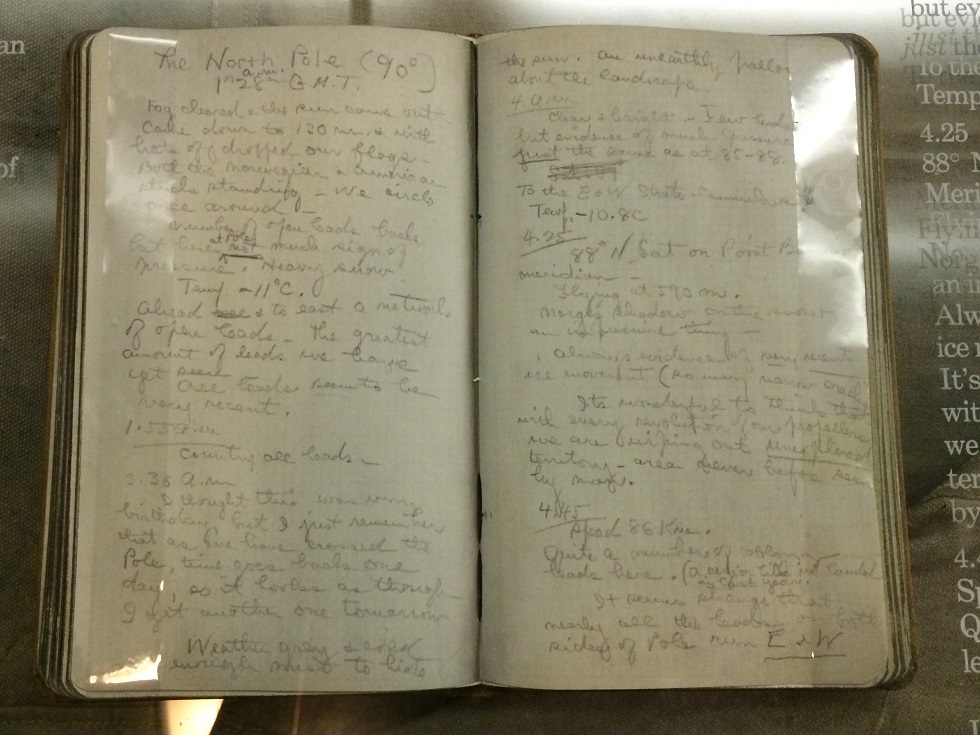

The following is a micro-essay that first appeared on Twitter—why not—that I’ve edited and pasted here in its entirety. The photos are all mine, taken at the Ellsworth Wing at the American Museum of Natural History.

**

Often I dream of desolate landscapes. Well, perhaps not desolate so much as isolated—great untouched swathes of pine forests, remote islands in Lake Superior where you could go as long as you wanted without seeing another human.

I love humans, and I love human interactions, but I still find myself regularly coming back to these thoughts—they calm and settle me, thinking of being out there on the land, envisioning people doing this sort of thing. Sure, there is a wave of mostly-true-but-also-incredibly-staged television programming celebrating people who live off the land, homesteading, and being hard-handed in a way that I am most certainly not, but that’s not what I dream of: the trees, mostly, the landscape as it melts away to the horizon.

I had a big group of friends when I was a kid, and even the neighborhood punks who I hated—they assaulted me with the chant “Robby Russell has no muscle!” from their private school bus when I would walk home from school—were still okay enough to invite to games of hide-and-go-seek tag or kick-the-can or Vampire Hunters (a game I invented where we teleported by stepping through a twin-trunked tree acting as a portal to a land where the dead ruled). But that neighborhood was a prison, too, and I didn’t even know it. The world, what was going on in it, was so far removed from my daily life that while, yes, I lived in a perpetual state of cartoony, innocence-driven bliss, I wouldn’t have even been able to tell you who the president was when I was a kid. Or why things like that mattered. My parents wanted to remove me from the troubles of the world and let me enjoy existing, and while I don’t necessarily agree with that now, I’m thankful for it: I had a very ingenuous childhood full of Saturday morning cartoons and sleepovers and (very) used Star Wars VHS tapes playing on repeat.

Lincoln Ellsworth changed all that for me.

Lincoln Ellsworth changed all that for me.

I learned in middle school that this man, my Great-Great-Great-Great-Great-Great Uncle, was a polar explorer. In fact, he was one of the polar explorers of his or any other generation. He was, and still is, eclipsed by his contemporaries—most notably Amundsen and Byrd, who even the most casual of history buffs are familiar with—but Ellsworth did alright, too, good enough to have a section of Antarctica, a lake and a mountain, named after him. But here I was, a kid who had traveled the country a teeny bit by that point via Amtrak—although, still under careful guard of my parents—reading about the exploits of a relative not horribly far-removed from my nuclear world. I was enamored!

An example: Ellsworth, along with Amundsen and some others, piloted planes to 87° 44′ north, the northernmost latitude reached by a plane at that time—which, if you strip away all the niceties of modern society and think about being so removed with no way to contact anyone, no one to rely one but yourself, is a remarkable feat. But…one of the planes crashed. They spent weeks clearing off a runway on the snow and ice and making repairs before finally taking off, everyone else in the world already assuming they had been lost, only to return, triumphant and adored.

This adventure was recounted in his book Search, the first of a few books he wrote, and a book I had my local library send over from Detroit, a book I voraciously read that described the adventure in great detail, how harrowing it all was, and how they managed to overcome and survive. The book, but specifically Ellsworth as a human who once existed, a man so different from me or anyone in my family, hooked me. He was a revelation—the world was a revelation—the sceneries, the hardscrabble humans trying to make it their own, just barely surviving—and that is when I started becoming obsessed with landscapes. Westerns, which were once completely unbearable to me, suddenly became fascinating, compelling: Vastly different than the polar regions, yet not at all, really. These stories of mankind against the land, trying to survive, the land itself a character and unflinching in its indifference toward their survival, was the most captivating thing to me then. I couldn’t get enough.

Ellsworth also flew across the north polar region via dirigible, which garnered the first undisputed sighting of the geographic north pole—a pretty big deal.

Ellsworth also crashed again—a recurring theme of his expeditions, although, this time due to a fuel shortage—while piloting over Antarctica. It was only him and his pilot. They were unable to notify anyone of the landing, and were declared missing, presumed dead. They made it to Byrd’s abandoned camp Little America—how wonderful, that name—and were discovered nearly two months later via a British research vessel.

Ellsworth’s support ship was called the MS Wyatt Earp (left). The man had a support ship.

Ellsworth’s support ship was called the MS Wyatt Earp (left). The man had a support ship.

Ellsworth was made an honorary Boy Scout.

Ellsworth was awarded two—two!—Congressional Gold Medals.

Ellsworth was a member of the Polar Legion, a group which demanded leadership of an expedition which reached either the geographic north or south pole.

Ellsworth was a major benefactor of the American Museum of Natural History.

Ellsworth, riches amassed, bought an island and built his house/compound on it—boss!—living there until his death.

Ellsworth once said: “Not until, years later, I found my true interest in life did I discover that I could master a subject, no matter how difficult, if it helped me in what I wanted to do.” Indeed, Ellsworth mastered the desolate, the barren. He mastered the freezing cold and everything that the mighty earth threw at him. He survived. And to me, then—to me now, too—this is something I hold dear: Every day is a victory. Survival is not assured, and we have to work hard at it. I can trace my fascination with nature, with survival and the relationships that flourish and are destroyed when confronted with potential doom, when nature becomes too much, back to Lincoln Ellsworth and his quixotic search for the horizon.

I wish I could shake his hand.

Very informative and enjoyable read. Hope you’ll publish more of these in the future.